这一次,有何不同? ——新冠肺炎疫情后经济复苏的形状

导语

在最乐观的情况下,一旦解除疫情封锁,世界将恢复趋势增长。但较为悲观的预测是,短暂的复苏之后会是长期的衰退,或者说这次疫情的暴发会对一些国家的经济发展空间造成毁灭性的打击,这些国家经济复苏的起点会更低。

拉至底部,阅读英文原文

V形、U形、W形或L形?不,这些不是字谜的答案,也不是某种难以理解的密码学形式,而是描述当前这个被认为比19世纪末经济危机更严重的全球衰退可能如何演变的符号象征。每个字母代表GDP的图形轨迹。

GDP增速图 /视觉中国

随着世界经济经历GDP急剧下降和失业率的迅速上升,预测者一直在努力确定此次经济衰退的规模和持续时间。国际货币基金组织首席经济学家吉塔•戈皮纳斯的预测报告显示,2020年世界经济将萎缩3%,3个月前他认为萎缩为3.3%。假设新冠肺炎疫情提前达到高峰,且弥补性政策取得成功,2021年世界经济将强劲复苏,实现5.8%的增长。

IMF总部照片/视觉中国

这次经济下滑之所以如此特殊,是因为它是经过深思熟虑的政策行动:随着大部分经济活动的停止,政府采取降低经济效益和社会互动的措施,以遏制新冠肺炎疫情的扩散。4个字母符号中向下的一笔都体现了这一点。然而,各国政府都面临着巨大的压力,让经济增长尽快回到常态。

“V”形是最乐观的情况。它的下降阶段很快就会反弹,类似一种蹦床效应。“U”形意味着初始下跌后停滞期更长,但最终会恢复趋势增长。“W”形和“L”形更令人担忧。前者意味着短暂的复苏之后的进一步下滑。如果发生第二轮感染,就可能会出现再次的经济衰退。在欧元主权债务危机期间,许多国家都遭受了这种双倍(甚至三倍)衰退的折磨。“L”形趋势是最令人担忧的,因为它意味着经济发展不是因为疫情的封锁而暂时出现了停滞,而是被永久性地遏制了。工人和投资者的“创伤疤痕”可能会加剧这种影响。随着这些国家经济复苏的起点变得更低,各经济体将突然出现阶梯式下降。

中国经验

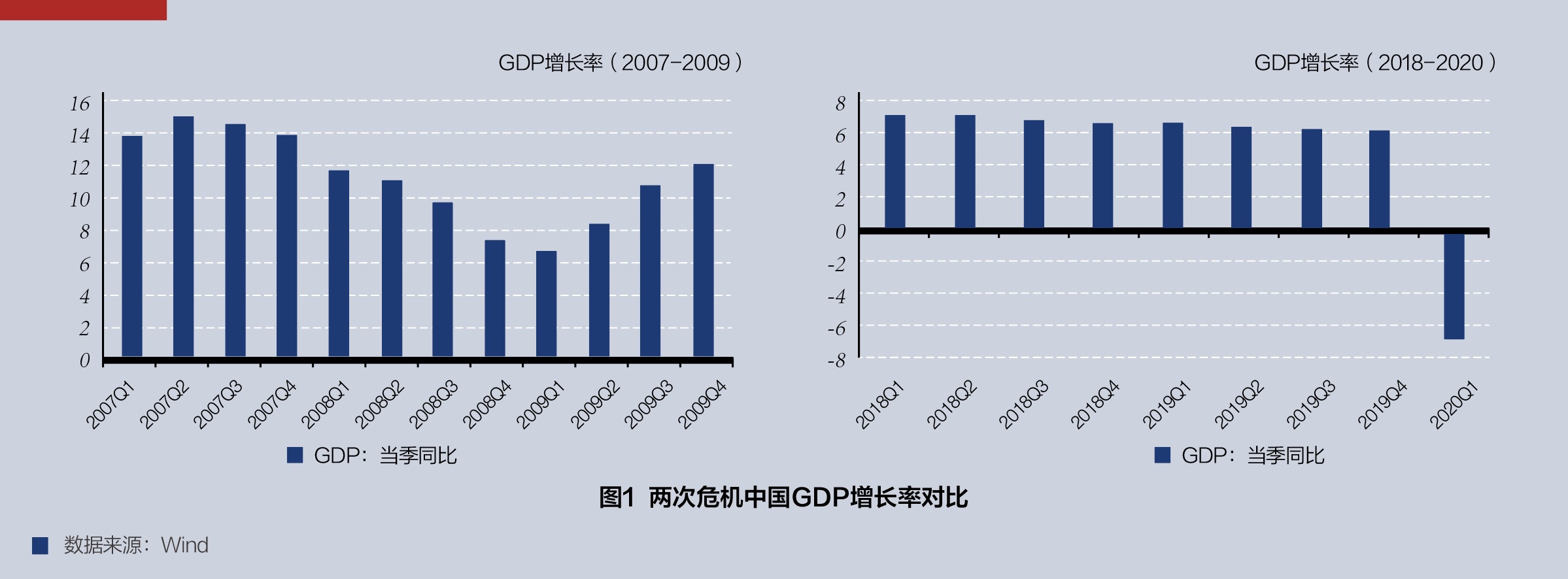

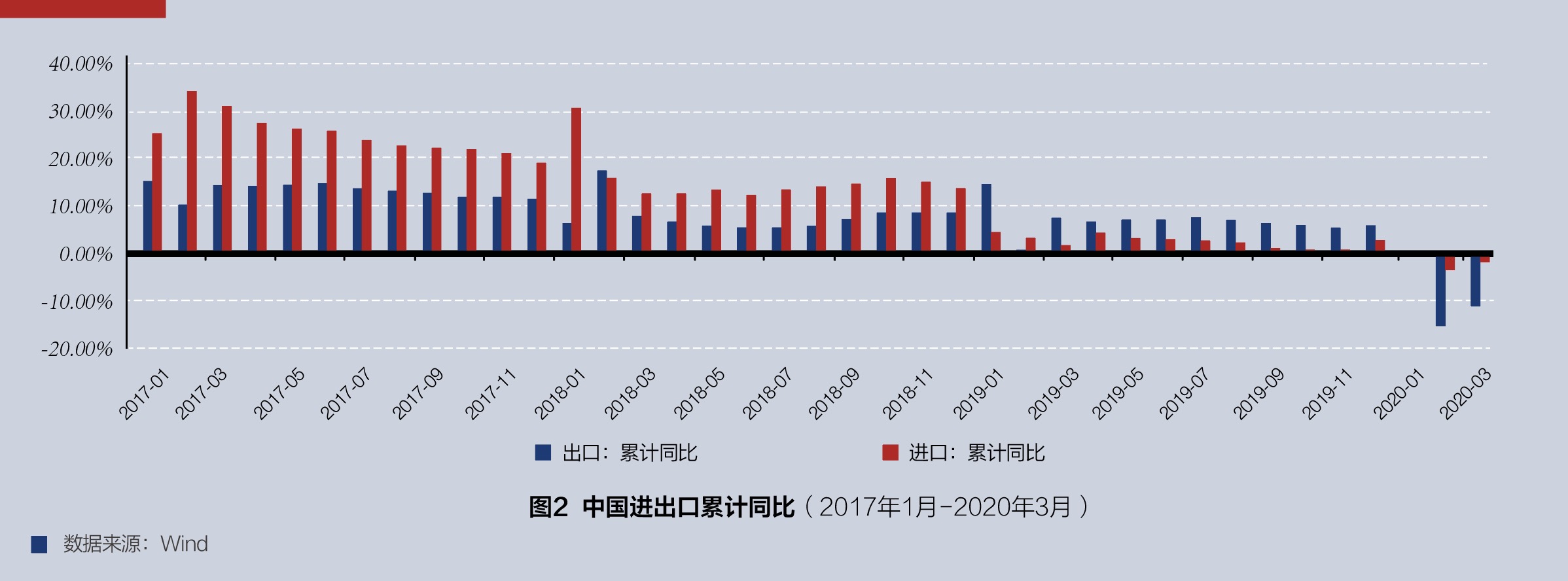

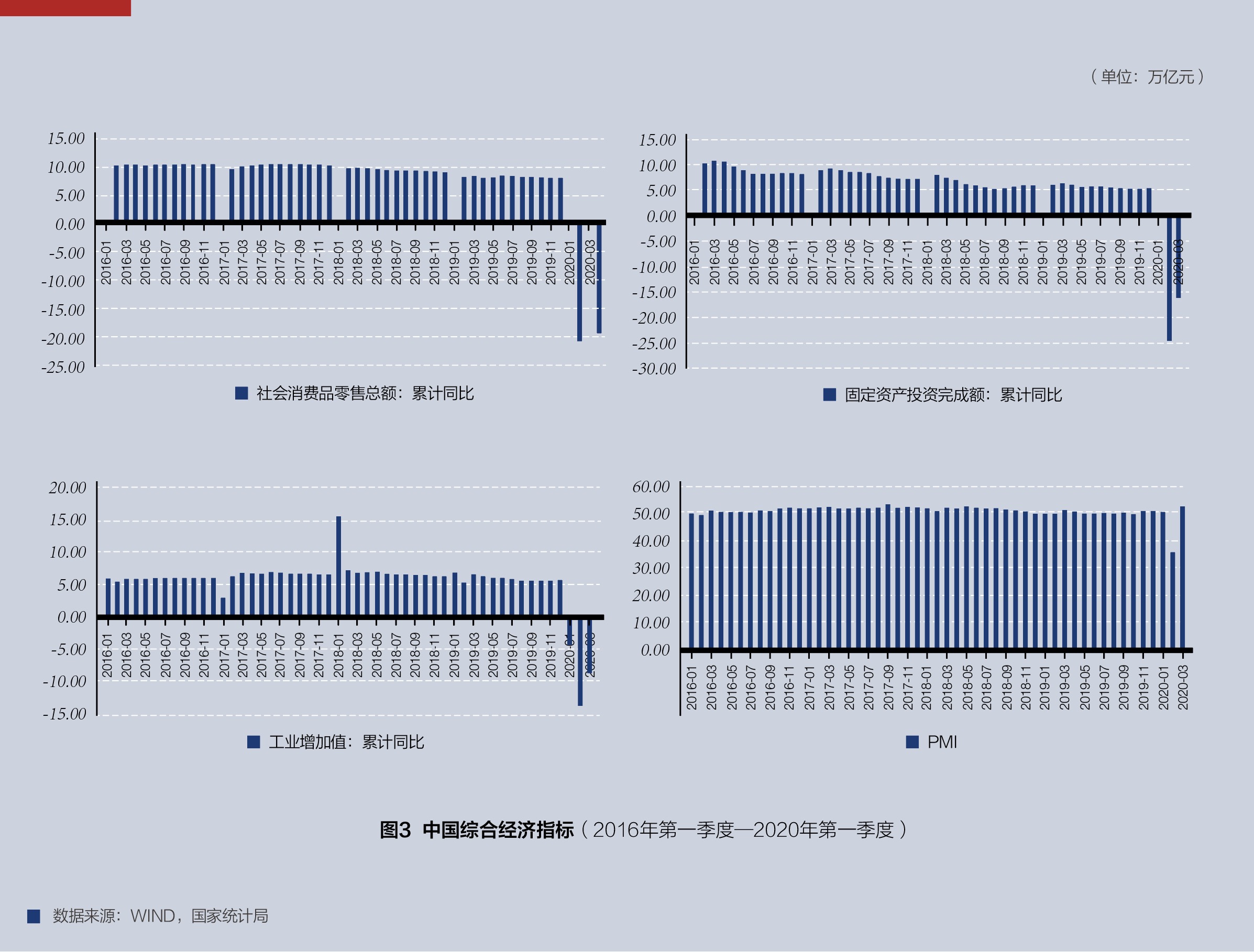

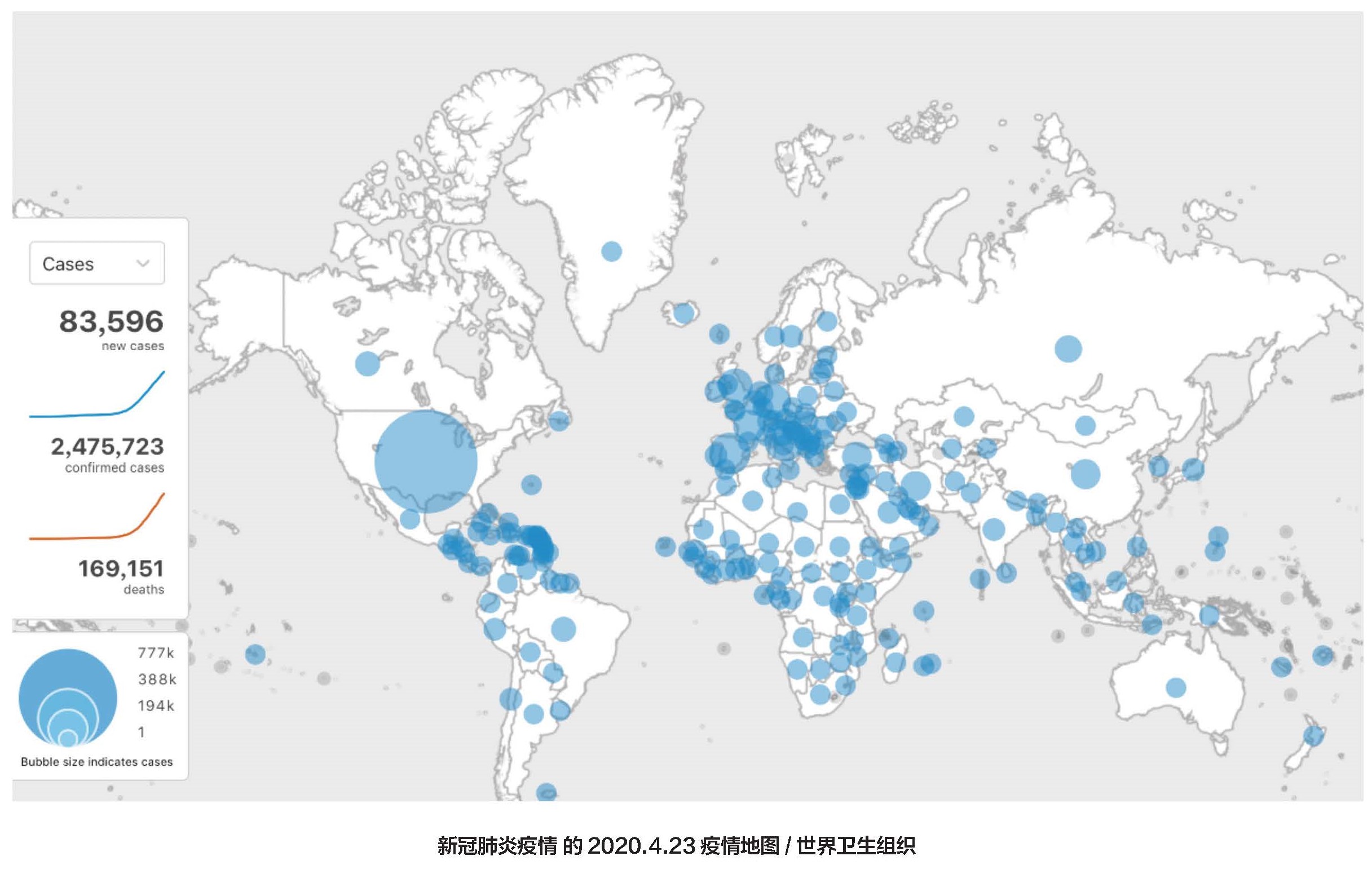

作为第一个因为疫情采取严格防控举措的国家,中国可以为其他国家或地区提供一些可见的经验。可以说,已经过去的低谷和2003年SARS的经验为经济复苏的乐观情绪打下基础。但是,此次的新冠肺炎疫情迅速成为一种全球现象,而非只局限于东亚;并且来自全球不同地方的负面反馈可能对中国造成更大的打击。在撰写本文时,第一季度GDP和许多其他经济指标已经发布(图1)。我们目睹了“V”形和其他形符号的第一阶段数据:40多年来,中国经济首次出现收缩,第一季度GDP同比下降6.8%;其中,湖北省同比下降了近40%。相比而言,2008—2009年金融危机时中国GDP增速下降,却没有出现像这次疫情下整个季度GDP下跌的情况。除了总体数据外,出口降幅远大于进口(图2)。以社会消费品零售总额衡量的两个重要的增长引擎:固定资产投资和消费,在前两个月大幅下滑,降幅超过15%(图3)。

从积极的一面来看,中国经济从3月份开始复苏。特别是,基于卫星图像显示人类活动的指标(如汽车、轮船等,还有工厂的停车场)表明,包括钢铁和汽车在内的制造业的复苏要快于服务业。这并不难理解,因为服务业需要大量人群共同参与生产和消费活动。此外,中小型企业受到的打击尤其严重,与所有行业的大型企业以及生产供应部门相比,它们的复苏速度较慢。但是,它们总共创造了中国60%的GDP,提供了80%的城市就业。因此,它们显然需要政府、金融机构、商业伙伴和社区的持续帮助,以求生存和恢复生产。

其他国家的展望

虽然中国继续表现出良好的经济发展趋势,但更艰巨的问题是,其他大国是否也可以像中国一样迎来经济复苏。在1930年代的大萧条时期,经济和社会的破坏严重而漫长,部分原因是美国政府在国内外施行了错误的政策:在国内,采取了紧缩而非激励的经济措施;在全球范围内,建立而非打破了贸易壁垒。

1930年,美国纽约,大萧条时期,一大批失业和无家可归的人等候在市政府外面,期待获得住宿和免费的晚餐。/视觉中国

现在的好消息是,主要经济体的政府迅速采取了广泛的货币和财政措施,用来支持企业和家庭。除了这些可能导致问题和风险的国内措施外,一种没有任何(经济)副作用的有力刺激措施是,取消对进口商品和服务征收的关税:哪怕仅仅暂时停止对贸易的限制,企业(尤其是中小企业)和消费者都会有所受益。然而,限制性因素包括:

• 服务业占比高,但恢复慢。在大多数经合组织国家中,服务业所占的比例要高得多。制造业占经济的比重不同:中国和韩国为30%,德国为20%,意大利为50%,西班牙和美国为11%,在法国和英国不到10%。正如在上文中国经验部分所指出的,这些行业比服务业更容易恢复。

• 交易暂停。由于封锁,大多数提供服务的企业(小型居多)被迫暂停交易,许多企业将无法生存。

• 旅游业的重要性。在国家和地区一级的主要目的地,预计都会出现收入大幅下降。

• 危机开始时公共债务的规模。危机开始时公共债务的规模将影响可能发生金融动荡的风险,意大利是最令人担忧的国家之一。

• 封锁的程度。它在一些地区程度一般,还是已经影响了整个国家。

• 封锁后行为的变化。比如航空业,办公室工作和某些休闲活动的需求是否会恢复到疫情前的水平?如果不会,其他活动会扩大以维持总需求吗?

• 疫情再一次爆发的可能性。由于只有很少一部分人感染了该病毒,疫情可能会再次暴发,需要进一步隔离。

• 全球产品和供应链的恢复速度。企业、行业和经济体之间的联系更加紧密,因此任何关键组成部分的崩溃都会导致整个链条的崩溃。危机后,一些国家可能会强烈地召回“关键”行业,但是这种产业搬迁昂贵耗时,整体经济效率也可能会受到影响。

• 合作的意义。在经济恢复过程中,全球产业链越快地恢复,总体经济就能越快地复苏。如果企业和行业之间有广泛的合作,这种可能性更大。

对全球经济的判断

此外,经济能否复苏很大程度上取决于决策者能否成功地实施刺激性政策。考虑到各种因素,中国经济复苏的形状很可能是“U”形,与中国进行广泛贸易的一些东亚和东南亚经济体也可能如此,但也都存在“ W”形的风险。一些服务密集型的欧洲国家容易呈现“L”形经济走势,出于同样的原因,美国也有出现“L”形走势的风险,除非在特朗普的鼓动下反对州长的意见占据主流,尽管这样做可能会导致经济走势变成“W”形甚至双“W”形。最大的不确定性是在尚未被病毒严重影响的大型发展中国家。

如果大多数大型发达经济体能够差不多在夏季之前控制疫情暴发,并在2020年第三季度开始恢复各项活动,那么到今年年底,全球有可能产生“V”形经济。然而,鉴于第二波疫情已经在一些亚洲国家出现(如新加坡),许多大型经济体中也有可能暴发第二轮疫情。因此,一个高于趋势增长率的“W”阶段可能会推迟到2021年上半年,甚至更晚。避免“L”形复苏符合所有人的共同利益。而要做到这一点,所有经济体之间的合作是至关重要的。G20,你听见了吗?

G20/2020年G20官网

What types of economic recovery are expected after the COVID-19 crisis?

Iain BEGG and Jun QIAN

V, U, W or L? No, these are not answers to a word puzzle or some obscure form of cryptography, but symbols to describe how the current global downturn, expected to be far worse than during the financial crisis of the late 2000s, might evolve. Each letter represents how the trajectory of GDP would appear on a graph.

With the world economy already experiencing a sharp fall in GDP and rapid rises in unemployment, forecasters have been struggling to work out how big it will be and how long it will last. Projections reported by Gita Gopinath, IMF chief economist, suggest the world economy will shrink by 3 percent in 2020, instead of the 3.3 percent growth forecast just three months ago. Assuming an early peak in the incidence of the virus (and that the countervailing policies are successful), it will recover strongly in 2021 to achieve growth of 5.8 percent.

The downturn is exceptional because it is a deliberate policy action. By putting substantial parts of the economy into hibernation, the aim is to reduce economic and social interactions so as to curb the spread of COVID-19. In each of the four symbols this is captured in the downward swing. Governments are, however, under considerable pressure to return to whatever passes for normality as quickly as possible.

"V" is the most optimistic scenario. Its downward phase will quickly be followed by a rebound: A sort of trampoline effect. A "U" shape would imply a more prolonged period of stagnation after the initial fall, but an eventual return to trend growth. "W" and "L" are more worrying. The former implies a short-lived recovery would be followed by a further downturn, as might occur if a second wave of infections occurred. During the euro sovereign debt crisis, many countries were afflicted by such double-dip (even treble) recessions. "L" is the most alarming, because it could arise if the aftermath of the lockdowns wipes out economic capacity permanently, instead of just suspending it. This effect could be exacerbated by the "scarring" of workers and investors. Economies would, at a stroke, have seen a step-change downwards, with trend growth resuming from a lower base.

China's experience

China, as the first country to enter lockdown, can provide some insights into what to expect elsewhere. It is, arguably, already past the trough and the experience of SARS in 2003 gave grounds for optimism and a "V" recovery. However, COVID-19 rapidly became a global phenomenon, rather than one largely confined to East Asia, and the negative feedback from different parts of the global economy could prove far more debilitating for China. As we write this piece, the first quarter GDP and a host of other economic indicators have been released. We have certainly witnessed the first stage of the "V" (or any of the other symbols): For the first time in more than 40 years, the Chinese economy contracted in a quarter, by 6.8 percent from the same period a year ago. Hubei Province, the epicenter of the outbreak, experienced a contraction of almost 40 percent. By contrast, China's GDP growth slowed during the 2008-2009 financial crisis, but it did not fall for the quarter as it did during the current outbreak. Going beyond the headline figures, exports dropped much more than imports. Investment in fixed assets and consumption (as measured by total retail sales of consumer goods), both important engines for growth, fell sharply (by more than 15 percent) in the first two months.

On the positive side, the Chinese economy started to recover in March. In particular, all indicators, including those based on satellite images showing the movements of people, cars, ships, etc., as well as parking lots of factories, show that manufacturing sectors, including steel and automobiles, are recovering faster than services sectors. These patterns are unsurprising, given that so many service activities require large groups of people to come together in the acts of production and consumption. In addition, SMEs (small- and medium-sized enterprises) were hit particularly hard, and have been recovering more slowly than large firms in all industries and along the product/supply chains. Collectively, they contribute 60 percent of China's GDP and 80 percent of urban employment, and clearly need continued assistance from the government, financial institutions, business partners and communities in order to survive and recover.

Outlook for other countries

Even if China continues to show favorable trends, a more daunting question is whether other major countries can emulate its recovery. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the damage to economies and societies was so acute and lengthy in part because governments adopted the wrong policies domestically and abroad: Domestically, instead of stimulus there were austerity measures; and globally, trade barriers were erected rather than broken down.

The good news today is that governments in major economies rapidly launched extensive monetary and fiscal measures to support firms and households. In addition to these domestic measures, which can lead to problems and risks down the road, a powerful stimulus that does not have any (economic) side effects would be to eliminate the tariffs imposed on imported goods and services; even a temporary pause in restrictive trade policies would help firms, especially SMEs, and consumers immediately. Nevertheless, reasons for concern include:

o The much higher share of personal services in most OECD countries. Manufacturing accounts for nearly 30 percent of the economy in China and South Korea, 20 percent in Germany, 15 percent in Italy, 11 percent in Spain and the U.S., and under 10 percent in France and the UK. As noted in relation to China, companies in this sector can resume more easily than in services.

o Most, often small, businesses offering personal services have been forced to suspend trading because of the lockdowns and many will not survive.

o The importance of tourism. Major destinations, at both national and regional level, can expect a big drop in income.

o The scale of public debts at the start of the crisis (Italy is among the most worrying) will affect the risks of subsequent financial instability.

o The extent of the lockdown and whether it was less intense in some regions or affected the entire country.

o Changes in behavior following the lockdowns: Will demand for aviation, office working, and certain leisure activities return to 'pre-corona' levels? If not, will other activities expand to maintain aggregate demand?

o With very small proportions of the population having been affected by the virus, fresh outbreaks, possibly requiring further quarantining, could occur.

o Another factor will be the speed of recovery of global product and supply chains. Since firms, industries and economies are more interconnected, a breakdown in any key component or link will lead to some degree of breakdown of the entire chain. While some countries may have a strong incentive to repatriate "critical" industries after the crisis, such relocation efforts are costly and take time to implement and overall economic efficiency may be compromised.

o More importantly, during the recovery process the quicker the global chains can be restored – more likely if there is broad cooperation among firms and industries – the faster economies can be back on track for growth.

Evaluation to global economy

Much, will, in addition, depend on how successful policymakers are in delivering their stimulus packages. Taking all such factors into account, China is likely to be a "U," and so are some East and Southeast Asian economies which have extensive trade with China, but there is a risk of "W." Some service-intensive European countries are most at risk of an "L," and the U.S. also risks an "L" for the same reason (unless the insurrection against State Governors being fomented by Trump prevails, though that could result in a "W" or even a double "W"). The biggest question mark is over large developing countries where the virus has not (yet) had so severe an impact.

If most of the largest and developed economies can more or less contain the outbreak by the summer and start the recovery process during the third quarter of 2020, then a global "V" recovery by the end of the year is possible. However, given the patterns of the second wave of the outbreak already observed in some Asian countries (Singapore), it is also possible that a second wave of outbreaks will occur in a number of large economies, and hence we will see a "W," with the higher-than-trend growth phrase postponed until the first half of 2021 or later.It is in the common interests of all to avoid an "L" shaped recovery, and to do so, cooperation among all economies is vital. Is the G20 listening?

Iain Begg – LSE

Iain Begg is a Professor at the LSE’s European Institute and co-Director of the Dahrendorf Forum.

Jun Qian – Fudan University

Jun Qian is a Professor of Finance and Executive Dean at Fanhai International School of Finance, Fudan University.

*本文经原作者授权,仅代表作者个人观点。